We all know—and certainly those who once sat in the gymnasium—that the Greeks invented philosophy: sophia, the love of knowledge. But fewer of us appreciate that they were among the first to cultivate rose gardens. Already in the 6th century BCE, lyric poets like Anacreon chose rose gardens as places for dialogue and reflection, believing that roses might help lead the soul toward ataraxia—a calm, untroubled state.

I’m not much of a philosopher myself, but I deeply admire those who practiced beauty as nourishment for both soul and mind. Roses are beautiful in every way: their sight, their fragrance, their silky petals when held in the hand. Even their thorns are part of the magic, sharpening our senses as we reach out.

What I especially love: among the earliest rose-lovers we know was a woman. In 7th–6th century BCE Greece, the famed poetess Sappho, devoted to Aphrodite, made the rose one of the goddess’s emblems. Beyond her Hymn to Aphrodite, fragments of her Song of the Rose survive. Here is a brief excerpt (translated by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1893):

For the rose, ho, the rose! is the grace of the earth…

In Greek the rose is called triantafyllo (“thirty leaves/petals”). But the ancient word for rose—rhódon—is at the root of rosa in Latin, and from there it blossomed across Europe: rose, rosa, Rose… in English, Italian, French, German, Bulgarian, Albanian, Swedish, Hungarian, and many more. Few other flower names are so widely shared.

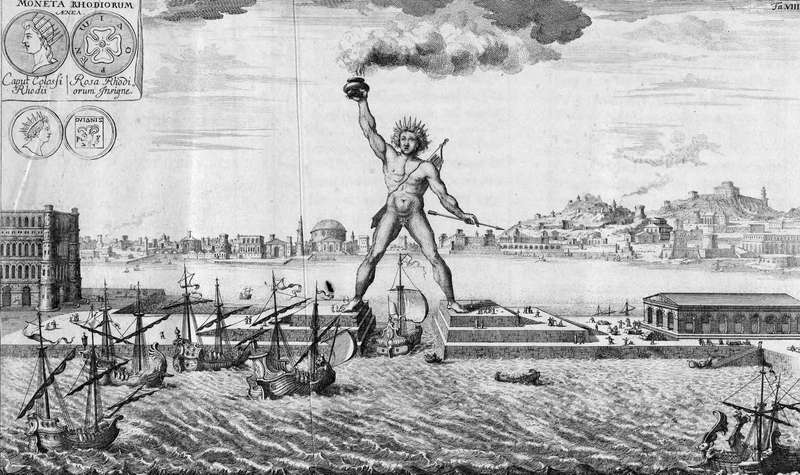

And then there is Rhodes—the island of roses. Its very name is linked to the ancient Greek word rhódon (“rose”), and legend tells of a nymph named Rhodo, who either gave her name to the island, or took it from it.

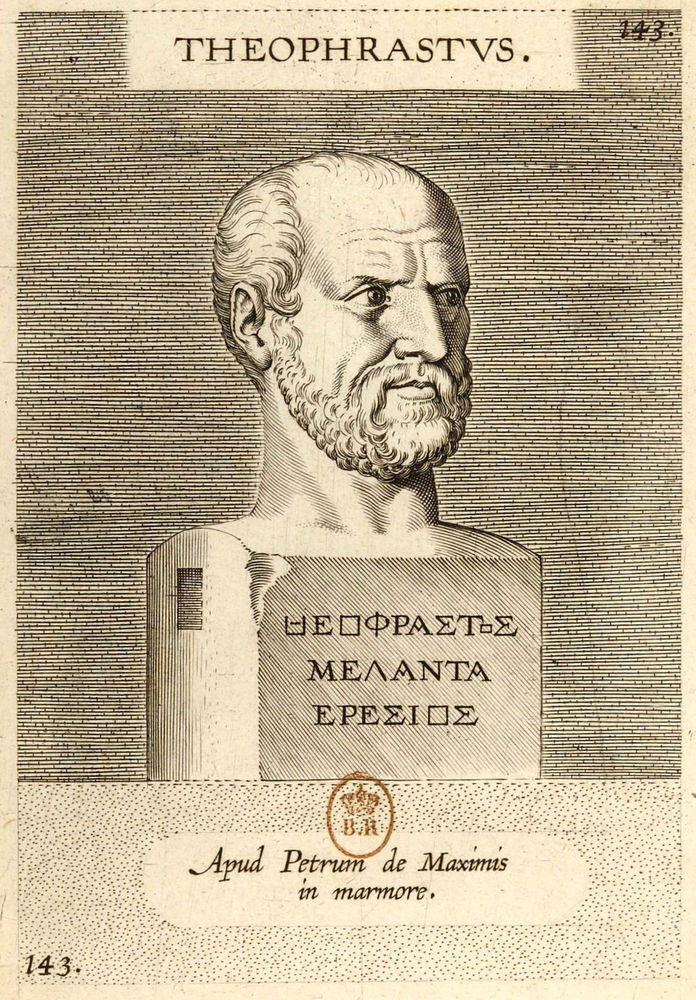

We also hear that Alexander the Great helped spread rose cultivation beyond Greece to Egypt and Europe. It is no coincidence: he was taught by Aristotle, a philosopher passionate about natural science. Aristotle’s student Theophrastus (4th–3rd century BCE), often called the “Father of Botany,” described roses and their varieties in his Enquiry into Plants, uniting the love of nature with the love of wisdom.

“The rose breathes of love,” Sappho told us millennia ago. And it still does. Roses remain at the heart of the world’s most precious perfumes, from Dior to Guerlain. They crown weddings, mark Valentine’s Day, honor remembrance, and celebrate love in all its forms.

So no—the rose is not only “stuff for ancient Greek lovers.” From ancient gardens to today’s bouquets, the rose has become one of humanity’s most enduring cultural treasures: the universal symbol of love.

Leave a comment